Surveying SARS-CoV-2

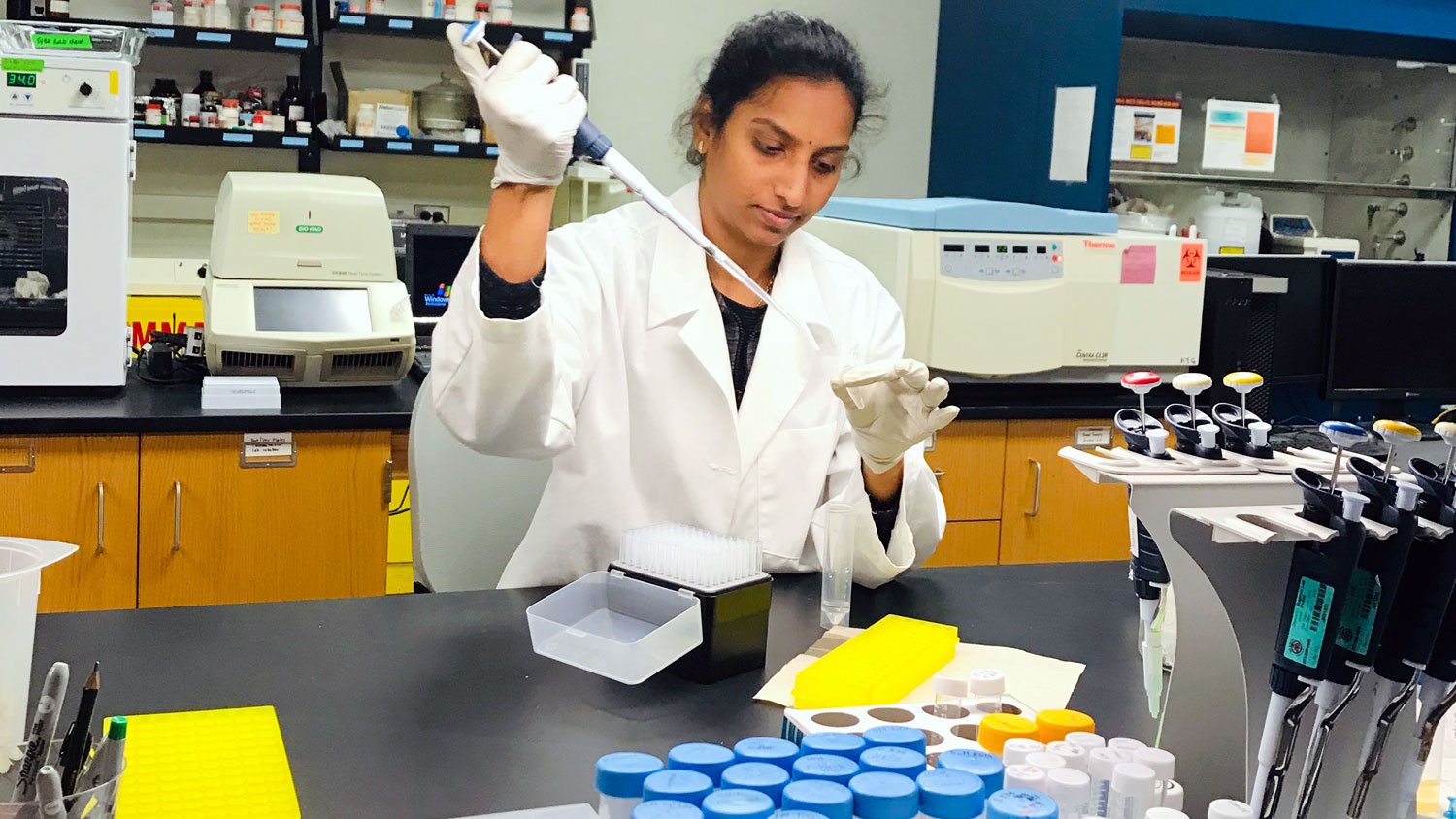

A researcher at the Gagnon lab at Southern Illinois University. Photo credit: Keith Gagnon

Creating a ‘one-stop-shop’ for critical pandemic data and insights

By now, the fact that the novel coronavirus “SARS-CoV-2” can, and has, mutated into different strains is common knowledge. However, at the start of the pandemic, there was a huge gap in what scientists understood about how the virus behaved and evolved.

With a dearth of COVID-19 samples available to test in early 2020, scientists were racing against the spread of the virus to gather and evaluate enough data to draw meaningful conclusions. In addition to the massive undertaking required to gather samples, distribute them to labs, and shift lab priorities nationwide to allow for this new focus, many of those engaged in this work across the country struggled to balance their own research with finding time to learn from the work of others. No one wanted to reinvent the wheel and do this work in a vacuum but there simply wasn’t time to search for what peers in other labs had done.

That’s where the Open Commons Consortium (Center for Computational Science Research Incorporated) came in. With support through Walder Foundation’s Chicago Coronavirus Assessment Network (Chicago CAN) initiative, the consortium dramatically expanded viral sequencing efforts in the Chicago region, and launched a data-sharing infrastructure for this and other epidemiological data.

“The idea is that if we can bring this sequencing data into our data commons, together with lots of other data about changes in mobility, people’s movement, environmental data, economic data, et cetera, we can better understand the dynamics of the disease in our community,” said Matthew Trunnell, principal investigator for the project and executive director of the Pandemic Response Commons Consortium.

The first step was to do the sampling. Under Trunnell’s leadership, researchers at the Gagnon lab at Southern Illinois University began receiving samples from the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPR), and researchers there were soon busily investigating bits of the genetic sequence of the virus.

In addition to making major contributions to the boots-on-the-ground sequencing work, the project also sought to combine the different data they and other groups collected into one, easily accessible place in order to expand overall understanding.

Indeed, much of what we know today about the intricacies of how the different strains have evolved and spread through Illinois has come from the Consortium and SIU’s combined efforts. “At one point, just this little lab at SIU had done more than half the sequencing in the state of Illinois,” Trunnell said.

Initially, the plan was for the SIU lab to test samples provided at random from the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) with a broad goal of simply learning whatever they could, but Trunnell said that as the virus began mutating more rapidly, the work became more urgent.

“Over the course of the pandemic, some of these variants really became of concern—first was the one that showed up in the U.K., then another one in Brazil, and then, of course, the Delta variant, which first appeared in India. Even before the Delta variant ever showed up in the U.S., we knew it was going to be very infectious. Once that was on the horizon, the health department started sending us the more unusual samples since they knew those were more likely to be of concern. Our goal really shifted into surveillance,” Trunnell said.

Even once the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began working more closely with the IDPH to collect and track state samples from Illinois, Trunnell said their work still left holes to fill on a local level, as the CDC does not track samples by zip code. That means state health authorities are still relying on other labs, like the one at SIU, to be able to map out where different variants of the virus are appearing in Illinois and how it is traveling through different communities.

Now that this first official project is nearing completion, Trunnell said he is excited to see what modeling his group may be able to do with the data they’ve gathered. The Consortium is also hard at work ramping up communications and community outreach efforts so that they can more clearly tell the story of the data to other researchers, as well as to the media and the general public.

“There’s lots of data available, but statistics are hard and messy. Interpretation of data is easily skewed. We really want to focus on strategic communication and data storytelling so that we can explain and educate,” said Trunnell.

Get more stories like this delivered to your inbox.

Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.